By Robyn Stewart, ANR Agent and County Extension Coordinator, Lincoln County

While we love the long days of summer and spending time at the barn, Georgia’s summer heat can be intense. The average heat index during the summer months is around 99.7°F, and in direct sunlight, it can feel up to 15°F hotter. Temperatures this high can have significant impacts on horse and human health and comfort and should affect decisions regarding workload, turnout, and other management factors.

It’s been shown that horses heat between 3 and 10 times faster than humans in hot weather (Geor et al., 1995). Other studies have shown that horses that are exercising can elevate core temperature around 1.3°F per minute. Even if you feel comfortable in the heat, your horse may be at risk when exercising in hot, humid conditions.

Table of Contents

- Defining Heat: Temperature, Relative Humidity, and Temperature-Humidity Indexes

- Cooling Mechanisms

- Fluid Losses

- Thirst Mechanisms

- Electrolyte Losses

- Electrolyte Supplementation

- Feeding Electrolytes

- Hydration and Dehydration

- Heat Stress and Stroke

- Anhidrosis

- Cooling Hot Horses

- Management Tips

- Heat Acclimation

- Special Considerations

- Don’t Forget the Human

- References

Defining Heat: Temperature, Relative Humidity, and Temperature-Humidity Indexes

Four key factors influence how heat affects horses and humans:

- Temperature – The measure of how hot or cold it is, reported in Fahrenheit (°F) in the U.S.

- Wet–Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) – A measure of heat and humidity that indicates how effectively sweating can cool the body.

- Humidity – The amount of water vapor in the air, expressed as relative humidity (%), which compares current moisture levels to the maximum amount the air can hold at that temperature.

- Temperature-Humidity Index (THI) – A calculation that combines temperature and humidity to indicate how hot it feels outside. This is important because the body cools itself through sweating, and high humidity reduces sweat evaporation, making it harder to cool down.

If temperatures are high but humidity is low, sweat evaporates efficiently, making it easier to stay cool. However, when both temperature and humidity are high, cooling becomes more difficult, and the heat feels much worse than the temperature alone suggests. Two different mechanisms can be used to explain the impact of combined temperature and humidity on heat dissipation: THI and WBGT.

One option for evaluating the impact of combined heat and humidity is the Temperature-Humidity Index (THI). Calculating the THI is simple. The equation is:

Air temperature (°F) + relative humidity = temperature-humidity index

For example, if it is 86°F and 75% humidity out, the THI is 161. The American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) has suggested guidelines for adapting equine activities at different THI’s (U.S. Equestrian Federation, 2024).

- THI below 130 – Horses can regulate their body temperature effectively. Normal turnout and exercise are safe.

- THI between 130 and 150 – The risk of heat stress increases. Monitor your horse closely if you choose to ride, work, or turn out, and be sure to cool them down properly afterward.

- THI above 180 – Horses cannot cool themselves, making any work dangerous and potentially life-threatening.

More recently, the Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) Index has become the preferred method for evaluating conditions for FEI-sanctioned events. WBGT has been researched by the FEI since the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games (Marlin, D. et al., 2018). Rather than just relying on air temperature and humidity like the temperature-humidity index, the WBGT index considers both sun and wind also. WBGT index is measured using wet bulb temperature and black globe temperature, or by using a handheld device like the ExTech HT30. The equation to calculate WBGT index is:

WBGT index = 0.7 x Wet Bulb Temperature (°C) + 0.3 x Black Globe Temperature (°C)

The specific recommendations for working horses based on WBGT vary based on discipline. Some recommendations are standard for all disciplines, such as provision of facilities for cooling, scheduling to avoid most thermally stressful times of day, and contingency for extreme conditions. Other recommendations are discipline-specific, such as reduction in overall effort of cross-country according to conditions (eventing); shortened courses and heart rate limits (endurance), and reduction in overall effort of Marathon (driving) (Marlin, D. et al., 2018). One example of the FEI recommendations for the Cross-Country Phase of Eventing are as follows:

- WBGT under 28 – no changes to recommended format.

- WBGT of 28 to 30 – Some precautions to reduce heat load on horses will be necessary.

- WBGT of 30 to 32 – Additional precautions to those above to limit overheating of horses will be necessary.

- WBGT of 32 to 33 – These are hazardous climatic conditions for horses to compete in and will require further modifications to the competition.

- WBGT above 33 – These environmental conditions are probably not compatible with safe competition. Further veterinary advice will be required before continuing.

Cooling Mechanisms

Horses primarily cool themselves through sweating, which accounts for 65-70% of heat loss. Sweat is composed of water, electrolytes (sodium, chloride, potassium, and others), latherin (a protein that helps move sweat from the skin to the surface of the hair), and other compounds. As sweat evaporates, it absorbs heat from the horse’s skin, cooling them down.

However, the effectiveness of sweating depends on environmental conditions:

- Humidity – When humidity is high, the air is already saturated with moisture, reducing the evaporation of sweat. This means that even if a horse is sweating heavily, it may not be cooling effectively.

- Airflow – Air movement helps remove moisture-saturated air from the horse’s body and replace it with drier air, allowing more sweat to evaporate. Windy conditions or the use of fans can increase evaporation and improve cooling, even in humid weather.

It’s important to remember that sweating alone does not cool a horse—it’s the evaporation of sweat that provides the cooling effect.

Fluid Losses

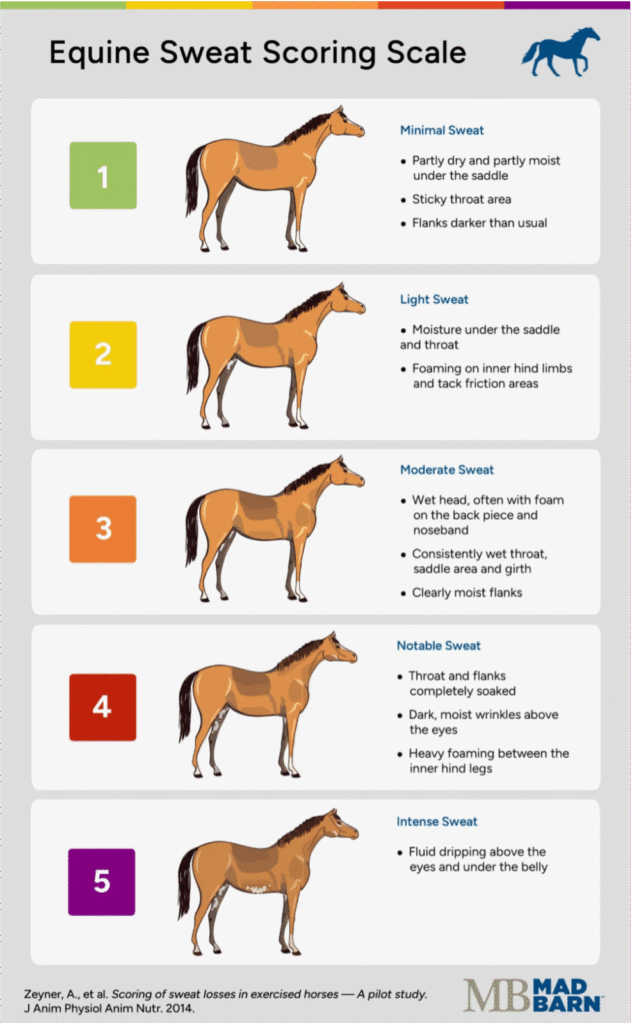

When sweat is our #1 cooling mechanism, maintaining proper hydration is critical. One major concern about managing horses in hot weather is the fluid losses due to sweat which can result in dehydration. In 2014, researchers from Martin Luther University in Germany developed a visual sweat loss scoring system, defining five scores of sweat correlating to body fluid losses, presented in Table 1. This study has been modified to show the visual markers by MadBarn (Figure 1). They estimate that during light to moderate work, horses lose anywhere between 0.2% and 3% of their body weight in sweat. Other studies estimate horses can produce 1 gallon of sweat every 15 minutes. Volume of sweat production is important when considering rehydration and electrolyte status, but there are a large number of factors that influence this such as animal size, THI, individual fitness levels, hydration status, and others.

Table 1: Sweat Loss Scoring System (Zeyner et al., 2014)

| Score | Visual Assessment | Sweat Losses (% of Body Weight) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Area under saddle partly dry, but flanks and throat dark and sticky | 0.2-0.7% |

| 2 | Wet area under saddle and on throat; small white foamy areas at the edges of saddle corners may occur; friction surfaces (reins and neck; between hind legs) may be white and foamy. | 0.7-1.2% |

| 3 | Bridle leaves wet impression around head (foam may be on noseband and crownpiece); throat and tack areas consistently wet; flank clearly wet | 1.2-1.5% |

| 4 | Throat and flank completely wet; moist dark wrinkles over eyes; pronounced foaming between hind legs on heavily muscled or fat horses | 1.5-2% |

| 5 | Horses dripping fluid above eyes and under belly | 2-3% |

Figure 1. Equine Sweat Scoring Scale

1. Minimal Sweat. Partly Dry and Partly Moist under saddle. Sticky under throat area. Flanks darker than usual.

2. Light Sweat. Moisture under the saddle and throat. Foaming on inner hind limbs and tack friction areas.

3. Moderate Sweat. Wet Head, often with foam on the back piece and noseband. Consistently wet throat. Clearly moist flanks.

4. Notable Sweat. Throat and flanks completely soaked. Dark, moist wrinkles above the eyes. heavy foaming between the inner hind legs.

5. Intense sweat. Fluid dripping above the eyes and under the belly.

modified from Mad Barn Equine Electrolyte Calculator

Thirst Mechanisms

The old adage, “You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make them drink,” holds particularly true in hot weather when horses may not consume enough water. In horses, thirst is triggered by fluid balance and electrolyte content. Fluid balance often triggers horses to drink in circumstances where light sweating occurs and the volume of electrolyte losses is low. In this case, the horse recognizes the fluid loss and drinks to replenish the total volume of water in the body. Thirst in response to electrolyte loss becomes a bit trickier. In humans, sweat is hypotonic. This means that when we sweat and lose water, the concentration of salt in our blood increases, which triggers us to drink. In contrast, horse sweat is hypertonic. This means that when the horse sweats and loses water, the concentration of salt in the blood remains the same and the thirst trigger doesn’t happen. This physiological difference makes proper hydration management key, as relying on a horse’s natural thirst response alone may not be enough to prevent dehydration in hot, humid conditions.

Electrolyte Losses

Sweating not only causes fluid loss but also depletes electrolytes, which are essential for cardiovascular, digestive, and cellular functions. Since horse sweat is hypertonic, it contains a higher concentration of electrolytes than the fluid inside the body’s cells. This means that as a horse sweats, it loses more electrolytes than it retains, increasing the risk of electrolyte imbalance if these minerals are not properly replenished. It is important to note that you should never give dehydrated horses electrolytes. If you give a hypertonic electrolyte solution (higher electrolyte content than what is in body fluid) to a dehydrated horse, water will be drawn from the horse’s body into the stomach and intestines until the concentration inside the gastrointestinal tract is the same as that in the body. Therefore, there is even less fluid in circulation which exacerbates dehydration.

The electrolytes lost in sweat include sodium, chloride, and potassium, with magnesium and calcium also being affected. To illustrate the extent of these losses, a horse with a sweat score of 3 can lose between 1.8 and 2.3 gallons of fluid during and after exercise. If a horse loses about 2 gallons of sweat, it also loses approximately:

- 22.4g sodium

- 40g chloride

- 9.6g potassium

- 0.8g magnesium and calcium

Simply providing clean water allows a horse to replenish fluid stores, but it does not replace the lost electrolytes. Without electrolyte replenishment, horses may struggle to recover fully, particularly in hot or humid conditions where they sweat profusely.

Electrolyte Supplementation

Electrolytes are minerals and are essential nutrients. As a baseline, horses should be supplemented with sodium and chloride (NaCl is table salt and provides both) at all times, regardless of sweating conditions. The baseline requirement for a 1,100lb horse at rest is around 10 grams of sodium and 40 grams of chloride per day (National Research Council, 2007). This maintenance need can be met by feeding 30 grams or two tablespoons of loose table salt per day. Horses that are in heavy sweating conditions will need additional salt supplementation to offset sodium and chloride losses, up to 1-2 tablespoons more than the maintenance amount. While other sources of salt like salt blocks can help supplement sodium and chloride intake, they may not be sufficient to meet daily requirements. Research suggests that horses consume more salt when offered it in a loose form, either top-dressed on feed or provided in a free-choice salt feeder.

A balanced equine diet consisting of forage, feed, and/or supplements should be able to meet the horse’s maintenance requirements for other minerals and electrolytes. As noted above however, those baseline requirements increase when horses sweat, and additional supplementation may be needed. Commercial electrolyte supplements are available that contain these minerals in the correct ratios to provide support recovery. When looking for electrolyte supplementation, consider products specifically designed for horses and avoid those that contain “dextrose” or other sugars. Be mindful if you are feeding supplemental salt (as noted above) in addition to electrolytes – many electrolytes do contain sodium chloride, and you’ll want to account for that when providing salt above the maintenance recommendation.

Feeding Electrolytes

Consider supplementing electrolytes for horses that meet the following criteria: Horses in moderate exercise, 3-5 hours per week, majority trot, some cantering and low-level discipline specific work (low jumps, cutting, etc; Horses in heavy or very heavy work, defined as 4+ hours weekly, including significant canter and gallop work, jumping, and technical exercises; horses working at high intensities or long durations and sweating profusely; and anytime conditions are extremely hot and humid, causing increased sweating (please note that this can also apply to pastured horses in hot climates).

Electrolytes can be fed 1-2 hours prior to exercise or provided in small amounts every 15-20 minutes after exercise. It can take up to 4 hours for the horse to fully hydrate and replenish its electrolyte stores. Electrolytes primarily come in two forms – powers and pastes. Electrolyte powders can be added to feed or mixed into water. It is important that if you provide electrolyte in the water, that you also provide a second bucket of clean water with no additives. Some horses will not drink at all if the electrolyte water is the only option. Electrolyte pastes are another option, but need to be accompanied by adequate water intake.

Hydration and Dehydration

Access to clean, cool (45-65°F), fresh water is critical for horses regardless of weather conditions. As a general rule of thumb, horses will drink between 8-12 gallons of water per 1,100lbs per day. This volume increases by 10-20% in hot, humid weather and is also influenced by diet, exercise, lactation status, and other factors. Horses grazing lush pastures or consuming soaked feed and hay naturally consume more water in their feeds, and may drink less fluid water as a result

Dehydration occurs when body tissues lack sufficient water to function properly. It can result from excessive water loss (sweating) or inadequate intake (not drinking enough water). Signs of dehydration include fatigue, decreased appetite, dry skin, increased heart rate, and colic. This is a serious condition, and a veterinarian should be contacted if these symptoms appear.

An easy test for checking hydration status is a skin tent test of the neck. If the skin bounces back quickly (within 1-2 seconds), the horse is well-hydrated. A delayed return to normal, or if the skin remains tented, the horse is likely dehydrated. A second tool is the capillary refill time (CRT). To check this, gently lift the horse’s lip and look at their gums, which should be a light pink and moist. Gently press on the gum using your finger, then remove it. The spot you pressed should be white and return to pink within 2 seconds. If the gums are tacky and there is delay (longer than 2 seconds) to refill the capillaries, the horse may be dehydrated. Depending on how severe the dehydration is, treatments might range from adding electrolytes to the feed to receiving fluids under the care of your veterinarian.

Heat Stress and Stroke

Access to clean, cool (45-65°F), fresh water is critical for horses regardless of weather conditions. As a general rule of thumb, horses will drink between 8-12 gallons of water per 1,100lbs per day. This volume increases by 10-20% in hot, humid weather and is also influenced by diet, exercise, lactation status, and other factors. Horses grazing lush pastures or consuming soaked feed and hay naturally consume more water in their feeds, and may drink less fluid water as a result

Dehydration occurs when body tissues lack sufficient water to function properly. It can result from excessive water loss (sweating) or inadequate intake (not drinking enough water). Signs of dehydration include fatigue, decreased appetite, dry skin, increased heart rate, and colic. This is a serious condition, and a veterinarian should be contacted if these symptoms appear.

An easy test for checking hydration status is a skin tent test of the neck. If the skin bounces back quickly (within 1-2 seconds), the horse is well-hydrated. A delayed return to normal, or if the skin remains tented, the horse is likely dehydrated. A second tool is the capillary refill time (CRT). To check this, gently lift the horse’s lip and look at their gums, which should be a light pink and moist. Gently press on the gum using your finger, then remove it. The spot you pressed should be white and return to pink within 2 seconds. If the gums are tacky and there is delay (longer than 2 seconds) to refill the capillaries, the horse may be dehydrated. Depending on how severe the dehydration is, treatments might range from adding electrolytes to the feed to receiving fluids under the care of your veterinarian.

Anhidrosis

Anhidrosis is a condition present in 2-6% of horses characterized by a limited ability to sweat, reducing their ability to cool themselves in hot conditions. Anhidrosis often occurs in horses living in hot, humid climates such as the Southeastern U.S. Horses with anhidrosis have sweat glands that fail to function when body temperature increases (such as when exercising or in hot, humid conditions). In chronic anhidrosis cases, the sweat glands themselves atrophy, or waste away. The exact cause of anhidrosis has not been found at this time, but is believed to be related to hormones and neurological factors.

Anhidrosis can appear as decreased sweating, a lack of sweat in specific areas of the body, or a complete inability to sweat. These horses are prone to overheating, heat stress, and heat stroke if not properly managed. It can develop gradually or appear suddenly in any horse, regardless of breed, age, gender, or fitness level. Horses with Pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID), or Cushing’s disease, may be at greater risk of developing anhidrosis.Anhidrosis can be diagnosed by a veterinarian and some treatment methods are available. Medical treatments through drug therapy, acupuncture, and herbs have been attempted but with little success, and there is not a current FDA approved treatment for anhidrosis. Dietary changes such as giving horses dark beer and supplements are generally not dangerous and have some anecdotal support, but are not supported by scientific research as a treatment for anhidrosis. Changing the management of these horses is the only therapy proven to help with anhidrosis. Moving horses to a cooler climate and environment can reduce anhidrosis by helping reduce high body temperatures and, in some cases, actually induce sweating again. In hot climates, horses must be managed to prevent high body temperatures from occurring, such as providing access to water sources to cool off, providing constant access to cool, fresh drinking water, and feeding electrolytes.

Cooling Hot Horses

Sometimes, working horses in hot, humid conditions is unavoidable. If a horse is hot (experiencing a body temperature over 101.5°F), there are a few things we can do to cool them off.

- End all exercise on a leisurely walk until the horse’s heart rate and respiration are close to normal.

- Remove all tack and equipment from the horse except for a halter.

- Provide shade and air flow. Get the horse into a barn or shady spot with good ventilation. Add a fan if possible to increase evaporation of the horse’s sweat.

- Apply cool water all over the horse’s body using a hose or buckets/containers. The FEI reports no advantage to concentrating water on any specific area, but suggests covering as much of the horse in cool water as possible.

- Do not waste time scraping water off the horse, but continuously apply more cold water to the horse.

- Sponging the neck, chest, legs, and belly with isopropyl alcohol can increase cooling since alcohol has a lower evaporative point than water.

- Add ice to the water you’re using to hose or sponge the horse to speed up your cooling efforts.

- Continue to provide fresh, cool water for the horse to drink.

Management Tips

Hot humid weather can mean we have to shift some of our management strategies. If possible, adjust your schedule.

- Work horses early in the morning or late at night when temperatures are lowest.

- Keep the workload light and take frequent breaks to allow the horse to cool down.

- Work horses in a well-ventilated, shady area.

- Provide opportunities for your horse to drink during exercise.

- Turn stabled horses out overnight, late in the evening, or first thing in the morning rather than during times of peak heat.

- Provide shade and shelter – it can be 15°F hotter in direct sunlight than it is in the shade.

- Keep fresh, cool water available to horses at all time.

- During extreme heat, consider stalling horses with fans and misters to help maintain their comfort.

- If you have to travel in hot weather, consider travelling overnight, or early in the morning, when it is cooler and there is less traffic.

- Avoid parking your trailer in direct sunlight, and do not allow horses to stand in a hot trailer.

- Make sure your trailer is as well-ventilated as possible – a cross breeze can be effective at improving air circulation.

Heat Acclimation

Studies have shown that horses are able to acclimate to hot, humid weather if they’re originally from cooler or drier climates. Horses need to exercise regularly in the heat for 14-21 days to become acclimated to the climate. Acclimation allows the horse to be more tolerant of the heat and improves work performance. Even if the horse is acclimated, be sure to monitor them to ensure their health and safety during work.

Special Considerations

Light-skinned horses that are turned out may be prone to sunburn, so keep an eye on them. Applying zinc oxide can protect sensitive skin from sunburn. Heat stress is possible in horses of all types and fitness levels, but some require special consideration. Prior research has shown that older horses reach increased body temperature and heart rates twice as quickly as younger horses (McKeever, 2002). There is also evidence that horses with high body condition scores (high body fat levels) struggle with thermoregulation and will overheat more quickly than those with lower body fat. Foals are at higher risk of developing heat stress and stroke in hot, humid conditions.

Don’t Forget the Human

A big priority for us should always be the care and well-being of our equine partners, but we can’t neglect to consider ourselves. Humans can experience dehydration, heat exhaustion, and heat stroke just like horses can. Be sure to drink enough fluids, stay in the shade when possible, wear sunscreen, eat, avoid working in the hottest part of the day, and consider using fans, misters, or cooling towels as needed.

References

Geor, R. J., McCUTCHEON, L. J., Ecker, G. L., & Lindinger, M. I. (1995). Thermal and cardiorespiratory responses of horses to submaximal exercise under hot and humid conditions. Equine Veterinary Journal, 27(S20), 125–132.

McKeever, K. H. (2002). Exercise physiology of the older horse. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Equine Practice, 18(3), 469–490.

National Research Council. (2007). Nutrient Requirements of Horses: Sixth Revised Edition. The National Academies Press.

U.S. Equestrian Federation. (2024, June 5). U.S. Equestrian competition update: Heat index.

Zeyner, A., Romanowski, K., Vernunft, A., Harris, P., & Kienzle, E. (2014). Scoring of sweat losses in exercised horses—A pilot study. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, 98(2), 246–250.